Recently, I completed a 6-week Improv 101 class and had a lot of fun trying out acting and improvisational comedy for the first time. I was initially curious about improv because its philosophy is very similar to design thinking and participatory design methods. Although improv comedy and design thinking may seem unrelated, they actually share important principles around creativity and collaboration.

As I learned more each week, I realized that the art of improv is not only about being funny, but also about behavioral observations and analysis, creating and deepening relationships, and understanding power dynamics, among other things.

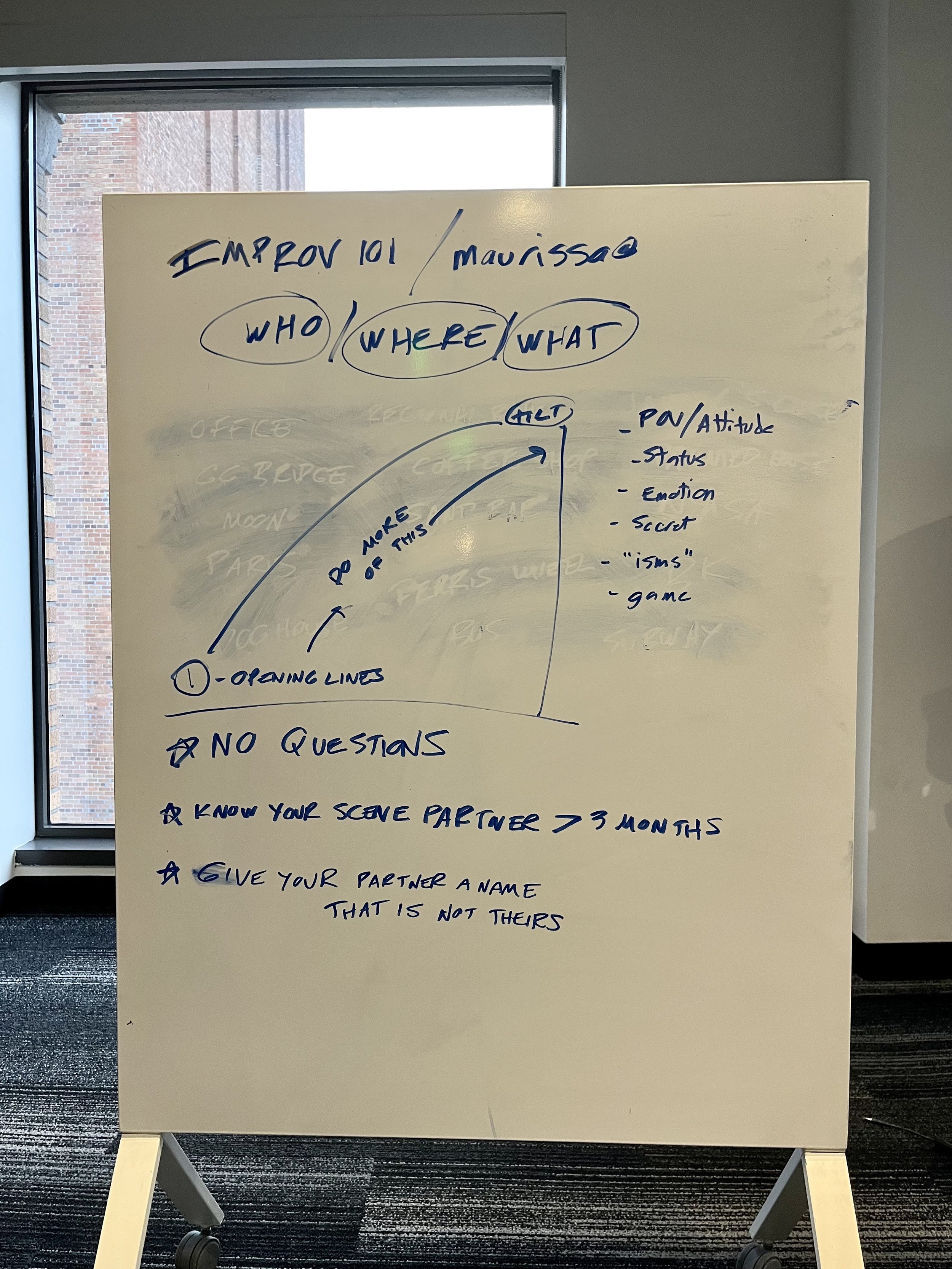

Rule-of-thumb: “Yes, and …” and avoid asking questions

The "Yes, and …" rule is a guiding principle in improvisational comedy. It advises improvisers to accept (”yes”) and build on what their partner has stated (”and”). The “Yes” portion of the rule encourages the acceptance of the contributions added by others, fostering a sense of collaboration, rather than denying the suggestion or ending the line of communication.

Another helpful rule is to avoid asking questions. This can be difficult to follow at first, since we often ask questions for clarification or to learn more. However, asking questions in an improv context does not build or expand on your partner's input. Instead, it’s best to rephrase questions into statements and hand them over to your partner to move the plot forward.

After we get comfortable with following the “Yes, and …” rule, it feels just like the idea generation process in design thinking. The feeling of letting go of control and embracing uncertainty is similar to rapidly iterating crazy new ideas without judgement in product design. It reminds me of a design workshop like crazy 8s, a fast sketching exercise that challenges people to sketch eight distinct ideas in eight minutes, with the goal of generating a wide variety of solutions to your design challenge. Creativity, collaboration, and collective imagination are the key spirits of improv, which are also qualities commonly shared in a good design brainstorming session.

Establish relationships and keep the plot moving

Every week, we learn about different techniques that help us establish partner relationships, set the scene, and keep the story progresses.

Naming and Identity: Assigning a name other than your partner's real name, such as "Josh," can help them establish a fictional character and give them permission to unleash their imagination. Assigning an identity, such as "captain" or "principal," also helps establish the scene by framing their roles. In this case, it can ground the scene in a specific setting, such as a ship, sports team, or school.

Social status: Assigning a rank to individuals in a group immediately shapes their relationships with each other. It influences how they choose to look, act, and respond to people with different ranks.

Holding on to a secret: When developing a scene with your partner, you can imagine that you are holding on to a secret. This secret could be something like "please don't leave me" or "I'm ashamed." Your partner may also be holding on to a secret. This approach is similar to design thinking, where a particular user group may have persistent, hidden motivations or needs that will manifest in different forms in a user journey. Understanding these "secrets" is key to unpacking people's behavior on the surface. This concept also occurs in psychotherapy, where certain internal motivations, fears, or desires drive consistent behavioral patterns. It is only when the client becomes aware of these persistent, hidden triggers that they can gain a new understanding about themselves and assess them objectively.

Choosing a posture: It's no surprise that your body language when sitting, standing, or walking can reveal a lot about your character. For example, leaning forward while sitting on a chair may make you seem attentive, nervous, or younger. Holding one hand under your chin may make you seem observant, judgmental, or thoughtful. In one class, everyone sat in a circle and took turns analyzing each other's posture while sitting on a chair. Then, based on the information inferred from the posture, each person started an opening line.

Overusing a word: You can choose to overuse certain words such as "like," "awesome," "honestly," or "actually." These words can become a part of your language system and act as signals that guide you as you establish and develop your character.

Emotion: Assigning a mood or emotion to your partner's character is a common way to establish their personality and the scene. For example, the opening line could be "You seem [sad, anxious, nervous, happy, scared]."

Relationship history: Setting the rule of knowing your partner for more than 3 months adds depth and shared memories to the relationship. This can be used to expand the story and shape both of your characters.

Our Improv instructor Maurissa holding the drawing co-created by our class

Status game as a social experiment

One of the most memorable exercises during class is the status game. You get assigned a card with a rank from 2 to ace, without knowing your own card. You have 15 minutes to socialize with everyone else, who you imagine you're at a party with, and figure out your rank. Then, everyone lines up from low to high, and you try to guess your relative ranking.

For example, you are more likely to approach and talk to someone who has a similar ranking as you. When people with significantly higher status approach you, you may appear more respectful and attentive, whereas you may seem more impatient or dismissive when people with significantly lower status approach you. Therefore, if you are either on the higher or lower ends of the rank, it’s relatively easier to tell based on the kinds of numbers that proactively approach you. But if you’re in the middle rank, such as 6 or 7, it can be harder to assess.

It's interesting to observe how people's actions can be influenced by the cards they receive and the power dynamics within relationships. It brought to mind the 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment, a psychological study that explored how roles, labels, and social expectations affected behavior in a simulated prison environment. While the status game is not as extreme as a prison environment, it highlights how status plays a significant role in shaping and defining relationships.

In addition, when someone is given a certain status, people often make assumptions based on that rank. These assumptions are used as a guide for the character and their partners to act in the story. For instance, status is often linked to wealth, political position, career, attitude, and lifestyle.

In a different situation, two people of different social status are waiting for a bus at a bus station. Their status may influence how they look, stand, and act. The person with the higher status may intentionally keep their distance from the person with lower status while waiting, and may be more relaxed since they can afford to take an Uber instead. On the other hand, the person with the lower status may appear more anxious and stressed because taking the bus is their only affordable option to get to work.

Final thoughts

The most counterintuitive moment for me was when I realized that all of these improv techniques are about giving structures and signals to help actors build their relationships as the story progresses. I used to think the plot came first, and that characters were just there to act it out. But in improv, I see that by focusing on the characters and exploring the complexity, nuance, and layers of their relationships, the story will naturally progress in interesting ways. This is similar to the logic behind producing reality shows. By inviting celebrities with distinct characters and capturing their interactions and relationships, an entertaining show can be created without the need for elaborate storylines or scripts.